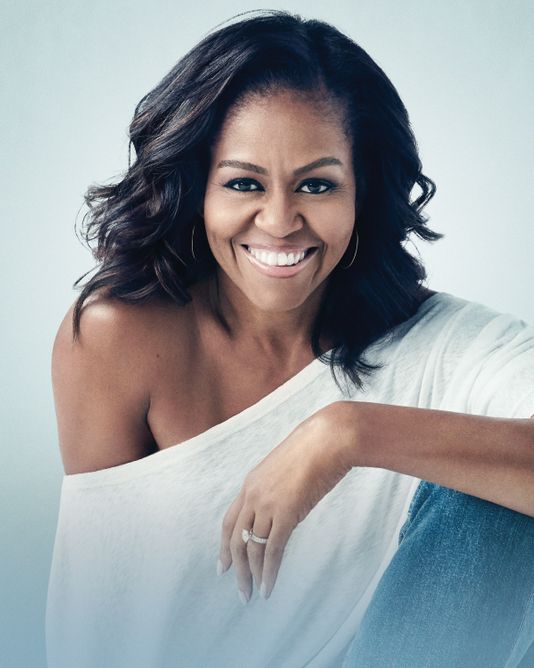

Dear Michelle Obama

Dear Michelle Obama,

I read your book recently, and I continually looked for details that might connect me to your story. As all Americans, I want to feel unique (which paradoxically makes me more alike than different to everyone else). Once I started reading, I barely stopped for four days. I relished reading because I felt I was hearing directly from you. It was a very intimate experience, which I can only credit to your skillful writing. I inserted myself into the story the way you would a novel, like picturing myself as Malia and my little sister as Sasha. (I was slightly shocked to find out Sasha is in fact my age and Malia is actually older than me). Later, I found a less abstract, albeit more convoluted, connection between my life and Becoming though.

You mention, “Cathy, one of my roommates, would surface in the news many years later, describing with embarrassment something I hadn’t known when we lived together: Her mother, a schoolteacher from New Orleans, had been so appalled that her daughter had been assigned a black roommate that she’d badgered the university to separate us.” Appalled, I discussed this with my friend Sydney. After I explained to her that Michelle Obama’s roommate’s mother (a distant association) at university was a racist teacher from New Orleans, Sydney informed me that Mrs. Alice Rodrigue taught at our school, Isidore Newman. Her daughter Catherine had even been Homecoming Queen. I felt dejected. This past fall, I had also been my class’s homecoming queen. I know Newman is not a model of Acceptance and Diversity, but clubs like Social Justice, Newomens, and Actions try to keep students aware and informed. I too am open-minded and participate in these clubs; after learning about Catherine though, I wondered: is it enough?

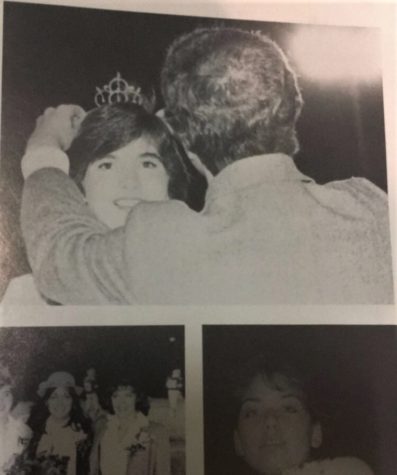

Next period, I rushed to my newspaper club meeting to share the connection Sydney made with my friends and fellow writers. We quickly assumed the role of investigative journalists and left the meeting room to talk to the head of alumni outreach, pull homecoming photos out of the archives, and scour yearbooks for pictures of Alice and Catherine Rodrigue. By the end of the day, our combined effort had recovered lots of pictures and information on the women, and I was not sure how I felt about them. I would be deceiving myself if I dismissed the issue and concluded that I am “better” than Alice and Catherine. We come from very similar backgrounds: upper class white women at Newman school in New Orleans. You recall your surprise upon arriving at Princeton University that “the only thing I needed to be vigilant about was my studies. Everything otherwise was designed to accommodate our well-being as students. . . We were protected, cocooned, catered to. A lot of kids, I was coming to realize had never in their lifetimes known anything different.” Newman is a school like that. I am of one of those kids who has been given everything. I have recognized my immense privilege before, but it is easy to forget, day-to-day, that all schools are not like Newman. I hate my school some days because I’m overworked or it’s too expensive or talk of improvement fails to be followed by action or friend groups initiate too much drama or because the classes are so small. But I recently reconnected with some old friends at Mardi Gras, and I realized that their schools are nowhere near as academically rigorous as Newman. The courses offered here are beyond what they may even be discussing. The teachers here bond with students over poems or science projects or research papers. The connections and opportunities available here are inaccessible elsewhere. Newman caters to us and nurtures us into high-level academics the way Princeton did for you. I attend the same school as your old college roommate, but the link between our backgrounds basically ends there.

I have fleeting worries that Newman’s environment made especially for me will spoil me for the “real world,” but I know that my privilege will persist into adulthood. Your dilemma about choosing a meaningful career when you wanted to leave Sidley & Austin resonated with me because I have faced similar privileged choices. “Fulfillment . . . [is] a rich person’s conceit” that I have looked unquestioningly for my whole life. Which classes will make me the happiest? Which summer activity will bring me the most enjoyment? What can I do for fun after school? Do I have time in my busy schedule to volunteer? Which colleges will provide me the best research opportunities? Most people cannot even consider their options, and happiness comes later; money weighs unfairly on life choices. My first taste of this struggle with money is only just occurring as I turn 18: my choice of college. I have to pick between the top school to which I was admitted and a less prestigious school for a better financial aid package. Even this is a privileged problem; either choice results in attending college. Similar to you at your first real job, I’m searching for meaning in my studies too. My focus in the past two years has been mothers. Understanding the economic responsibility of mothers, mother-child psychology, aspects of maternal medicine, and influential mothers in literature, like Toni Morrison’s Beloved and The Bluest Eye, are my greatest interests. You asked on your Instagram how everyone is in the process of Becoming, and, though I’ve barely just begun, mothers and children inspire me to learn and become a more useful version of myself. I want to attempt to use my privilege to solve mothers’ issues, like the disparity between black and white women’s maternal health care. I want to study economics to find solutions alleviating the phenomena of the gender pay gap and “mommy tax” that punish working women. I want to study psychology and sociology to find out why gender and maternal stereotypes infiltrate so many societies. I hope my early ability to make choices based on passion leads to positive change in the world.

I found my connection to you, but I know it was trivial. My life has been, and will continue to be, very different than yours. I admire your drive to help people, especially American children. Your book inspired me to learn more about my school and myself, recognize my privilege, and plan to affect change. The book is now a part of my Becoming story.

Laine Nowak

"How do you write like you're running out of time? How do you write like tomorrow won't arrive? How do you write like you need it to survive?" -Hamilton,...